Most courtroom movies are loud. They have slamming doors, dramatic speeches, and last-minute evidence that changes everything. Anatomy of a Fall isn’t like that. It’s quiet. Cold. Almost still. And that’s what makes it unforgettable.

The Death That Wasn’t an Accident

Sandra Voyter, a German writer living in the French Alps, finds her husband Samuel dead at the bottom of a staircase. The police call it an accident. The neighbors aren’t so sure. The media jumps in. And suddenly, Sandra is the prime suspect. No blood. No struggle. Just a body, a broken leg, and a mountain of unanswered questions. What follows isn’t a whodunit. It’s a whydunit. The film doesn’t care who pushed him. It cares about what broke between them. The marriage. The trust. The lies. The silence. The film spends more time showing Sandra staring out a window than it does showing lawyers shouting. And that’s the point.A Courtroom Like No Other

This isn’t an American trial. There are no juries of twelve. No lawyers cross-examining like they’re in a TV show. France uses an inquisitorial system - meaning judges investigate, not just oversee. Three professional judges sit together. A lay juror joins them. The trial isn’t about winning. It’s about uncovering truth. The courtroom scenes feel like watching someone slowly open a locked diary. Evidence isn’t presented in flashy bursts. It’s read aloud - letters, emails, journal entries. The prosecution doesn’t need to prove Sandra did it. They just need to prove she could have. And they do it by digging into her past: her affair, her writing, her silence after Samuel’s death. One of the most chilling moments comes when the prosecutor says, “This woman is bisexual, so that means all she knows is eat hot chip, kill husband, plunder book, and lie.” It’s not just a line. It’s a mirror. It shows how prejudice becomes proof in a system that’s supposed to be neutral.Sandra Hüller Doesn’t Act - She Exists

Sandra Hüller doesn’t perform. She breathes. Her face doesn’t change much. Her voice stays calm. But you feel everything. The grief. The anger. The fear. The guilt. She doesn’t cry in front of the court. She doesn’t beg for mercy. She just sits there, answering questions like someone who’s been waiting years for someone to finally ask the right ones. Her performance isn’t about big moments. It’s about the tiny ones. The way she hesitates before answering. The way she looks at her son when he says something innocent. The way she doesn’t look at the judge when she’s lying. You don’t know if she’s guilty. But you know she’s real.The Blind Son Who Sees Everything

Daniel, Sandra’s 11-year-old blind son, isn’t a prop. He’s the film’s moral center. He doesn’t see faces. But he hears everything. The tone of a voice. The pause before a lie. The way someone’s breath changes when they’re scared. In one scene, he tells his mother, “When we don’t understand what happened, we should try to understand why it happened.” That line isn’t just sweet. It’s the whole movie. The court wants to know what happened. The film wants to know why. The sound design makes this clear. During courtroom testimony, background noise fades. Voices sharpen. You hear what Daniel hears - not what the lawyers say, but what they mean. The film doesn’t show his face much. But you feel his presence in every silence.

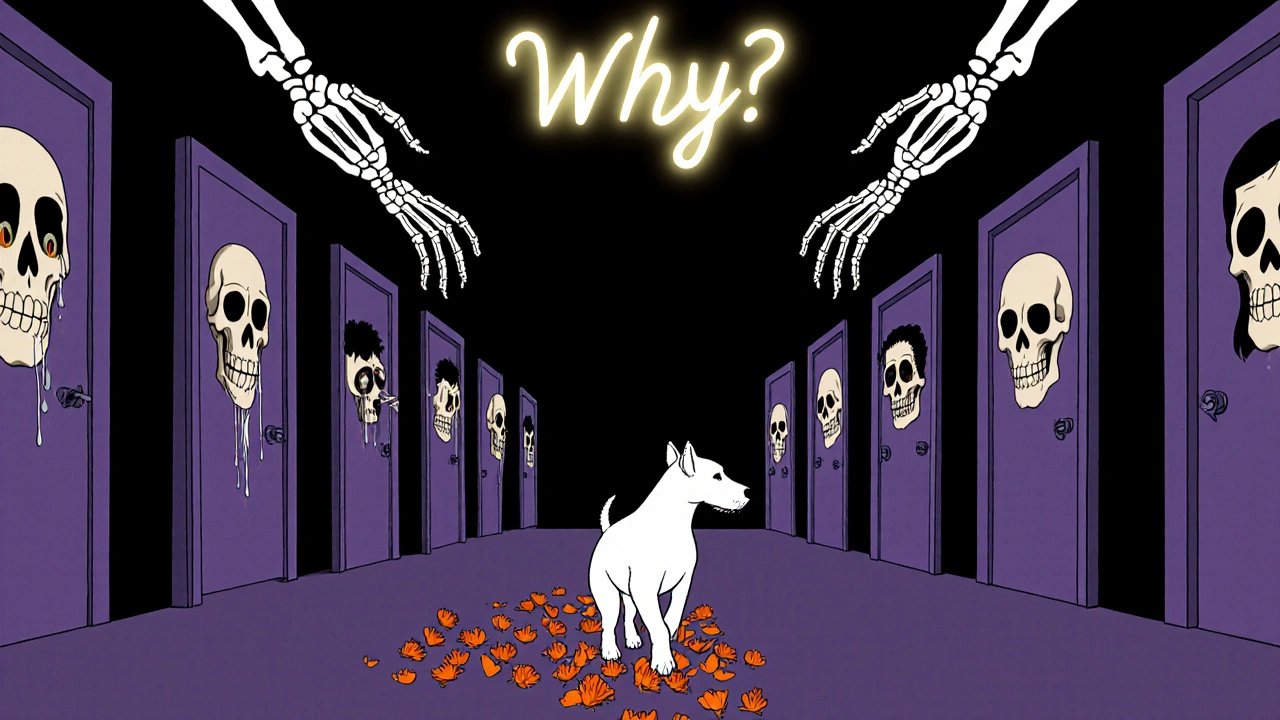

The Dog, the Dog, the Dog

Yes, the dog. You read that right. The family dog, a small white terrier, appears in the opening scene. It’s there during the investigation. It’s there in the courtroom. And it’s listed first in the closing credits. It’s not a joke. It’s a statement. The dog doesn’t lie. It doesn’t have motives. It doesn’t care about reputation. It just is. And in a story full of people twisting truth, the dog becomes the only honest character. People on Letterboxd have spent hundreds of reviews arguing about it. Some call it genius. Others call it pretentious. Either way, you won’t forget it.Why It Feels Too Long - And Why That’s the Point

At 151 minutes, this film doesn’t rush. Critics say it drags. Some viewers say it’s boring. But that’s exactly what the director, Justine Triet, wanted. Real trials aren’t fast. Real grief isn’t neat. Real marriages don’t collapse in a single scene. The length forces you to sit with the discomfort. To sit with Sandra. To sit with the silence. To sit with the fact that you might never know what really happened. Roger Ebert gave it 3.5 out of 4 stars and wrote, “Sometimes, it seems like 151 minutes is more than this story needs.” But then he added, “And yet, I wouldn’t cut a single second.”Is It Accurate? Yes - Even the Weird Parts

Some viewers say the French legal system looks ridiculous. Judges reading novels? No cross-examination? No dramatic outbursts? It’s not ridiculous. It’s real. French law doesn’t rely on lawyers to prove guilt. It relies on judges to dig into lives. Letters, diaries, therapy notes - all are fair game. The prosecution didn’t need to prove Sandra killed Samuel. They just needed to prove he was unhappy. And she was the one who stayed silent. Legal professionals in France confirmed the procedures match Article 307 of the French Code of Criminal Procedure. Even the way the trial is conducted - the panel, the lack of jury, the focus on written evidence - is accurate. This isn’t Hollywood fiction. It’s French reality, filmed with precision.

What It Says About Us

This isn’t just a movie about a murder. It’s about how we judge people we don’t understand. Sandra is a writer. She’s German. She’s bisexual. She’s emotionally distant. She doesn’t cry on cue. She doesn’t beg for sympathy. And because of that, people assume the worst. The film asks: Do we convict people because of what they did? Or because of who they are? It’s not about whether Sandra is guilty. It’s about whether we’re willing to live with uncertainty. Whether we can accept that some questions don’t have answers. Whether we can let someone be complicated - without needing to label them.Where to Watch It

You can find Anatomy of a Fall on Mubi in North America and Netflix in Europe. It’s also part of the Criterion Collection, which includes a 47-minute behind-the-scenes documentary and the director’s full commentary. If you’ve ever wondered what a truly thoughtful legal drama looks like, this is it.Why It Still Matters

As of 2025, 47 American law schools use this film in criminal procedure courses. Forensic psychology programs cite it in peer-reviewed studies. Why? Because it doesn’t give you answers. It gives you questions. It shows how bias becomes evidence. How silence becomes guilt. How love and resentment live in the same room. And how sometimes, the truth isn’t something you find - it’s something you survive. It’s not a thriller. It’s a mirror. And it’s one of the most honest films about justice in the last decade.Is Anatomy of a Fall based on a true story?

No, the film is fictional. But it’s grounded in real French legal procedures and societal attitudes toward marriage, gender, and truth. The director, Justine Triet, drew inspiration from real cases where personal history was used to convict someone without direct evidence.

Why is the film set in the French Alps?

The snowy, isolated setting mirrors the emotional coldness of the marriage. The landscape isn’t just backdrop - it’s a character. The silence of the mountains reflects the silence between Sandra and Samuel. The cold makes every breath visible, just like every unspoken word in their relationship.

Does Sandra kill her husband?

The film never confirms it. The prosecution builds a case based on motive and character, not proof. The defense argues reasonable doubt. The verdict is left ambiguous - and that’s the point. The film isn’t about guilt. It’s about perception.

Why does the blind son play such a big role?

Daniel represents truth without bias. He can’t see people’s faces, so he hears their intentions. His questions cut through legal theater. His presence reminds the court - and the audience - that justice isn’t about appearances. It’s about understanding what’s hidden beneath them.

Is the film too slow for most viewers?

It demands patience. If you want fast cuts and explosive moments, this isn’t for you. But if you’re willing to sit with discomfort, listen to silence, and let meaning unfold slowly, it becomes one of the most powerful experiences in modern cinema. Many viewers say they didn’t like it at first - but thought about it for days after.