There’s something about a film score that sticks with you long after the credits roll. It’s not just background noise-it’s the heartbeat of the movie. A single theme can make you feel like you’re flying, falling, or fighting your way through a war zone, all without a single word being spoken. The best film scores don’t just accompany the story-they become part of it. They’re the reason you still hum the Star Wars theme while brushing your teeth, or why you get chills when the first notes of Also sprach Zarathustra kick in during a sunrise scene.

John Williams: The Master of the Main Theme

John Williams is the undisputed king of cinematic music. He didn’t just write scores-he built sonic identities for entire franchises. His work on Star Wars (1977) didn’t just elevate the film; it rewrote the rules of what a sci-fi movie could sound like. Before Williams, space operas often leaned on electronic sounds or sparse orchestration. He brought back the grandeur of 19th-century Romantic composers like Wagner and Tchaikovsky, giving the galaxy far, far away a mythic, almost biblical weight.

The Star Wars main theme isn’t just memorable-it’s structurally perfect. It opens with a bold brass fanfare, then unfolds with sweeping strings that feel like ships gliding through stars. It’s instantly recognizable, emotionally powerful, and perfectly timed to the visuals. Williams repeated this magic with Jaws (1975), where just two alternating notes created one of cinema’s most effective horror tools. No monsters needed. Just two notes, played slowly, and suddenly every swimmer in the ocean felt like prey.

His themes for Indiana Jones, E.T., and Schindler’s List aren’t just music-they’re emotional anchors. The violin solo in Schindler’s List, played by Itzhak Perlman, carries the weight of unspeakable loss. It doesn’t tell you how to feel. It lets you feel it, raw and quiet.

Hans Zimmer: Modern Epic, Digital Soul

If Williams defined the 20th century’s sound of film, Hans Zimmer reshaped the 21st. Zimmer doesn’t write melodies the old way-he builds sonic worlds. His score for The Dark Knight (2008) replaced traditional orchestration with a single, distorted cello note, amplified and layered until it sounded like a monstrous heartbeat. That sound became the Joker’s sonic signature. No costume, no laugh-just a vibrating string that made audiences feel like the city itself was cracking.

With Inception (2010), he turned time into sound. The iconic “BRAAAM” sound-created by slowing down a recording of a brass chord-doesn’t just signal a dream collapse. It makes you feel time stretching, warping, slipping away. It’s not just music; it’s a physical sensation. And in Interstellar (2014), he used a pipe organ in a cathedral to mimic the vastness of space. The organ’s deep, rumbling tones echoed the gravitational pull of black holes. You didn’t just hear the score-you felt it in your chest.

Zimmer’s genius is in knowing when to strip things down. In Dune (2021), he used throat singing, Taiko drums, and distorted vocal harmonies to create a sound that felt ancient and alien. There’s no melody you can hum-but you’ll never forget it. That’s the point. He’s not trying to make you whistle. He’s trying to make you feel lost in a desert of time.

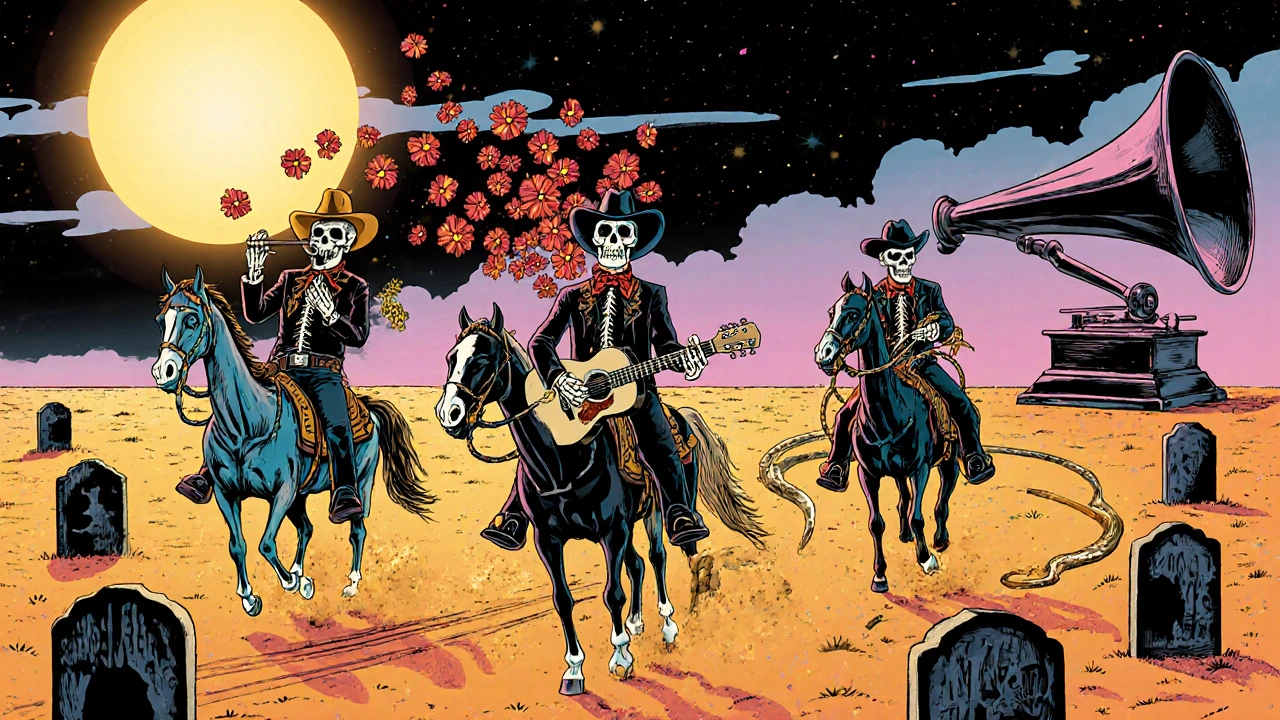

Ennio Morricone: The Sound of the Wild West

Before Zimmer and Williams, there was Ennio Morricone. His scores for Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns-especially The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)-turned the American frontier into a mythic, operatic landscape. He didn’t use traditional orchestras. He used whistling, electric guitars, whip cracks, and human voices humming in eerie harmonies. The main theme? A whistle, a yodel, a twanging guitar, and a choir singing like monks in a desert cathedral. It’s absurd. It’s brilliant. It’s unforgettable.

His work on Cinema Paradiso (1988) showed his range. That score is pure nostalgia. A simple piano melody, layered with strings, makes you feel the weight of a lifetime spent watching movies. It doesn’t need drums or brass. Just a child’s wonder, captured in notes.

Morricone proved that a film score could be experimental and still be loved by millions. He used unconventional instruments because they told the story better. A gunshot in a duel wasn’t just a sound effect-it was a musical note. The silence between notes? That was the tension.

James Horner: Emotion in Every Note

James Horner had a gift for turning quiet moments into emotional earthquakes. His score for Titanic (1997) is the most famous example. “My Heart Will Go On” became a global hit, but the real power lies in the orchestral themes that weave through the film. The Celtic flute, the swelling strings, the heartbeat-like percussion-it all builds toward the moment the ship sinks. You don’t need to know the plot to feel the tragedy.

He did the same with Apollo 13 (1995). The score is restrained, almost clinical. No big themes, no soaring violins. Just a quiet pulse, like a spacecraft’s oxygen monitor ticking. It makes the danger feel real, not dramatic. Horner knew that sometimes, the most powerful music is the one that doesn’t shout.

His work on Braveheart (1995) gave the Scottish rebellion a voice. The bagpipes, the war drums, the choir chanting in Latin-it didn’t just accompany the battle scenes. It made you feel like you were standing in the mud, sword in hand, ready to charge.

Howard Shore: Building Worlds with Sound

Howard Shore didn’t just score The Lord of the Rings trilogy-he built a musical language for Middle-earth. He created over 100 leitmotifs-repeating musical themes tied to characters, places, and cultures. The Shire has a gentle, folk-inspired tune played on accordion and flute. Mordor’s theme is a crushing, dissonant choir chanting in a made-up language. Gondor’s theme is a noble brass fanfare that grows stronger as the story progresses.

Shore’s score is so detailed, you can listen to it without watching the films and still understand the plot. He didn’t just write music. He composed a cultural history. The dwarves have a hammer-and-anvil rhythm. The elves have haunting, wordless vocals. Each culture has its own instrument palette. It’s the most ambitious orchestral project in film history, and it works because every note serves the world.

Why These Scores Endure

What makes these scores timeless isn’t just their beauty-it’s their purpose. They don’t just match the mood. They define it. They turn a character’s grief into a melody, a battle into a rhythm, a journey into a progression. A great film score doesn’t just support the story-it becomes the story’s soul.

These composers didn’t just write music. They created emotional blueprints. They knew that a single note, played at the right moment, could make a viewer cry, cheer, or hold their breath. That’s why you still listen to these scores on repeat, long after you’ve forgotten the plot. They’re not just background. They’re memory.

What Makes a Film Score Legendary?

There’s no formula, but the best ones share common traits:

- Thematic memory-you can hum it, even years later

- Emotional precision-it matches the scene without overpowering it

- Innovation-it uses instruments or techniques no one else tried

- Integration-it feels like part of the film, not something added on

- Timelessness-it doesn’t sound dated, even decades later

Some scores use traditional orchestras. Others use synthesizers, choirs, or found sounds. The tool doesn’t matter. What matters is whether the music makes you feel something deeper than the visuals alone ever could.

Modern Trends and the Future of Film Music

Today, film scores are more diverse than ever. Composers like Ludwig Göransson (Black Panther) blend African rhythms with electronic beats. Hildur Guðnadóttir (Joker) uses cello drones to mirror mental unraveling. Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross (The Social Network) turned glitchy electronics into a portrait of genius and isolation.

But the core hasn’t changed. Whether it’s a full orchestra or a single synth line, the goal is the same: to make the invisible visible. To turn emotion into sound. To make a story unforgettable.

What’s the most iconic film score of all time?

Many would argue it’s John Williams’ Star Wars main theme. It’s been played at Olympic ceremonies, quoted in pop songs, and recognized by people who’ve never seen the movie. Its combination of bold brass, sweeping strings, and mythic structure makes it instantly memorable and emotionally powerful. But iconic is subjective-Jaws’ two-note theme, Morricone’s whistling western tune, or Zimmer’s "BRAAAM" from Inception are just as powerful in their own way.

Do film scores still use orchestras today?

Yes, but not always alone. Big-budget films like Oppenheimer and Dune: Part Two still use full orchestras because they offer unmatched emotional depth. But modern scores often blend orchestral elements with electronic textures, field recordings, or vocal samples. The goal isn’t to replace the orchestra-it’s to expand what it can do. Hans Zimmer’s Dune score, for example, uses a 120-piece orchestra alongside throat singing and Taiko drums.

Can a film score make a bad movie good?

Not usually, but it can make a mediocre movie unforgettable. Think of Blade Runner 2049. The film had mixed reviews, but the score by Hans Zimmer and Benjamin Wallfisch turned it into a sensory experience. The music carried the emotion the script couldn’t. A great score doesn’t fix a broken story, but it can give it soul. That’s why people still watch films with weak plots-they’re there for the music.

Who’s the most underrated film composer?

Jerry Goldsmith deserves more recognition. He scored classics like Alien, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and The Omen. His Alien score is a masterpiece of tension-using metallic clangs, deep choirs, and pulsing rhythms to make space feel like a tomb. He didn’t chase fame, but his work shaped decades of horror and sci-fi soundtracks. If you’ve ever felt dread in a sci-fi film, you’ve heard Goldsmith’s influence.

How do composers start working on a film score?

They usually start by watching the film with the director and discussing the emotional arc. They identify key scenes that need musical emphasis-like a character’s first moment of hope, or the climax of a battle. Then they develop themes tied to characters or places. Some write piano sketches first. Others experiment with sounds on a computer. The process varies, but the goal is always the same: to find the sound that belongs to the story.

Where to Start Listening

If you’ve never listened to film scores on their own, start here:

- Play Star Wars from beginning to end-just the score, no movie.

- Listen to The Dark Knight soundtrack while walking at night. Notice how the music makes the city feel alive.

- Put on Cinema Paradiso and close your eyes. Let the piano carry you.

- Try Dune on headphones. Feel the bass shake your chest.

- Play The Good, the Bad and the Ugly while cooking. You’ll find yourself whistling it by dinner.

These scores aren’t just music. They’re the invisible characters in the movies you love. And once you hear them for what they are, you’ll never watch a film the same way again.