Before the 1980s, Chinese cinema was mostly state-approved stories with clear moral lessons-heroes triumphed, villains were punished, and history was rewritten to fit the party line. Then came a group of filmmakers who had spent their youth in the countryside, chopping wood, serving in the army, or surviving the Cultural Revolution. They didn’t just want to make movies. They wanted to see China-really see it-and show the world what they’d lived through.

The Birth of a Movement

In 1978, the Beijing Film Academy reopened after being shut down for twelve years during the Cultural Revolution. The class that walked in wasn’t made up of teenagers. These were men and women in their mid-to-late twenties, many already scarred by years of forced labor and political turmoil. Among them were Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige, Tian Zhuangzhuang, and Huang Jianxin. They weren’t just students. They were survivors with cameras. Their films didn’t start with scripts. They started with images. Zhang Yimou, who had been a photographer before film school, didn’t just direct-he shaped every frame. In Yellow Earth (1984), Chen Kaige filmed the dusty hills of Shaanxi Province in wide, silent shots. No music. No dialogue. Just earth, sky, and a lone girl walking. It wasn’t about storytelling. It was about feeling trapped. The land didn’t give. It swallowed. And the people? They were small against it. This was new. Before them, Chinese films were propaganda. Now, they were poetry wrapped in pain.The Aesthetic of Silence and Color

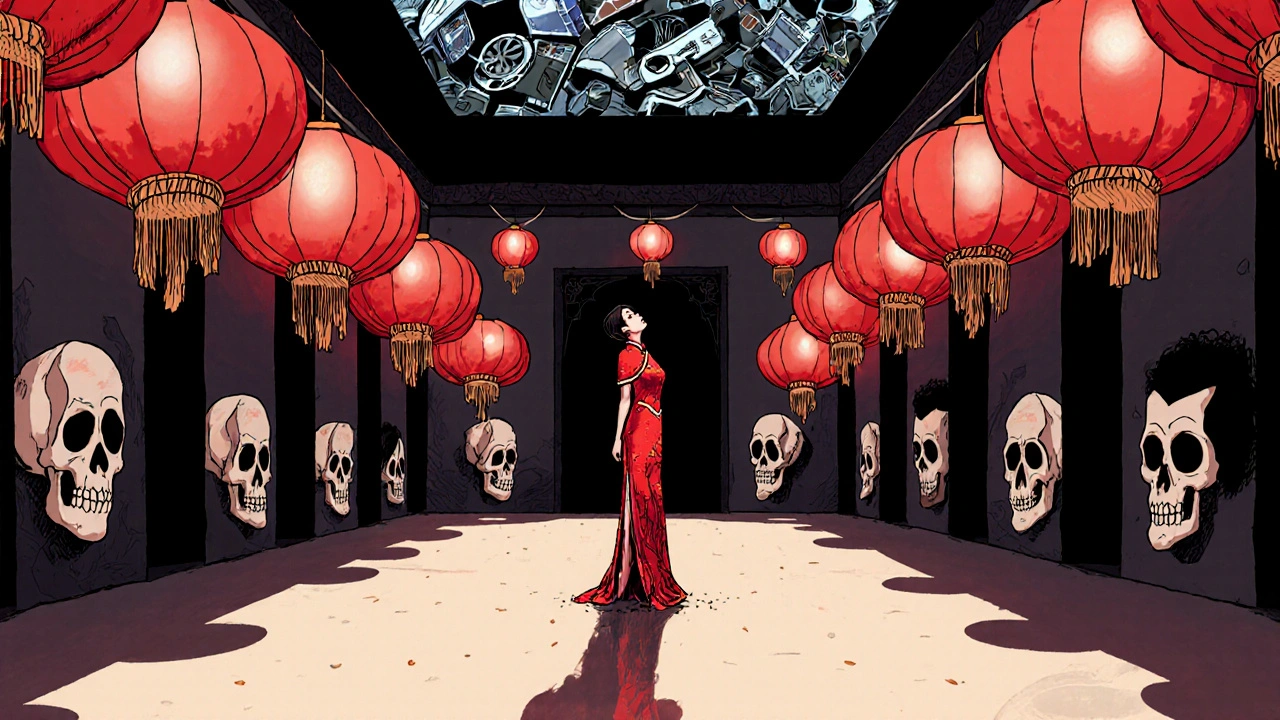

The Fifth Generation didn’t use words to criticize. They used color. In Ju Dou (1990), the dye factory glowed with impossible reds and yellows. The fabric wasn’t just cloth-it was blood, passion, forbidden desire. The colors were so loud they screamed what the characters couldn’t say. Zhang Yimou, who shot the film himself, turned the factory into a prison painted in hues of rage. Then came Raise the Red Lantern (1991). Four women in a courtyard, competing for the attention of one man. The lanterns-bright red, hanging in perfect rows-weren’t decoration. They were signals. A lit lantern meant favor. An unlit one meant death by neglect. The camera never showed the sky. The walls were always closing in. Every shot felt like a cage. These weren’t just beautiful images. They were coded messages. The censors couldn’t ban a red lantern. But they knew what it meant.International Fame, Domestic Silence

While these films were banned or barely shown in China, they won awards in Europe and North America. Red Sorghum took the Golden Bear in Berlin. Farewell My Concubine won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. For the first time, Chinese cinema wasn’t invisible-it was celebrated. But back home, people couldn’t buy the DVDs. The films circulated in smuggled VHS tapes and pirated copies. On Douban, China’s film forum, Farewell My Concubine has a 9.0/10 rating-higher than almost any Hollywood film-but only 380,000 reviews. Compare that to Wolf Warrior 2, a patriotic action film from 2017, which has over 2 million. The difference isn’t quality. It’s access. The Fifth Generation’s films were funded by Japan, France, and Germany-not the Chinese government. That’s why they could show the Cultural Revolution’s cruelty, the silence of rural poverty, or the hidden queer identity of a Beijing opera singer. The state didn’t pay for them. So they couldn’t control them.

What Made Them Different

Before the Fifth Generation, Chinese films were like textbooks. Clear. Predictable. Safe. These directors studied Godard, Antonioni, Truffaut. They didn’t want to teach. They wanted to unsettle. They used long takes. Silence. Extreme close-ups. They shot on location with cheap film stock and made it look like art. Zhang Yimou, working with almost no budget, used natural light to turn dust into gold. Chen Kaige let his actors breathe. No melodrama. Just presence. Their trauma became their technique. The way a woman stares out a window in Yellow Earth isn’t just acting. It’s the look of someone who’s been told her life doesn’t matter. And yet, she’s still there.The Legacy That Outlived Them

By the mid-1990s, the window closed. The government tightened control. Funding dried up. The Fifth Generation had to adapt-or fade. Zhang Yimou shifted. He made Hero (2002), a visually stunning epic about unity and sacrifice. It was beautiful. But it was also state-approved. He later directed the 2008 Beijing Olympics opening ceremony-a spectacle of synchronized movement, red banners, and perfect geometry. It was the Fifth Generation aesthetic, now repurposed as national pride. Chen Kaige went further. His 2023 film, The Volunteers: To the War, is a patriotic war drama funded by the state. The man who made Farewell My Concubine-a film about identity, performance, and forbidden love-is now making films about soldiers and sacrifice. The Fifth Generation didn’t disappear. They changed. Some became icons. Others became tools.

Why It Still Matters

Today, Chinese cinema is dominated by blockbusters. Superheroes. Military triumphs. Nationalist myths. The kind of films that make billions but say nothing. But if you want to understand China-not the version sold on state TV, but the one lived in silence-you still need to watch these films. The Fifth Generation didn’t just make movies. They turned cinema into a mirror. And for a brief, dangerous moment, China looked into it. Their influence is everywhere. Jia Zhangke’s quiet, long-shot documentaries? That’s Chen Kaige’s Yellow Earth in the digital age. The way color is used in House of Flying Daggers? Pure Zhang Yimou. Even the sweeping drone shots in modern Chinese epics? They’re just high-tech versions of those dusty hills in Shaanxi. The Fifth Generation didn’t win because they were the best technicians. They won because they were the first to say, in a language no one else dared use: This is what we saw. This is what we felt.What to Watch Next

If you want to understand this movement, start here:- Yellow Earth (1984) - Chen Kaige’s silent masterpiece. The birth of the Fifth Generation.

- Red Sorghum (1987) - Zhang Yimou’s first directorial effort. Raw, bold, and unforgettable.

- Ju Dou (1990) - A tale of passion and repression, painted in blood-red.

- Raise the Red Lantern (1991) - A chilling portrait of power, gender, and silence.

- Farewell My Concubine (1993) - A sweeping epic of identity, art, and survival.

Who are the main directors of the Chinese Fifth Generation?

The core directors are Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige, Tian Zhuangzhuang, Wu Ziniu, and Huang Jianxin. They all graduated from the Beijing Film Academy in 1982, after studying together in the class of 1978-the first class admitted after the Cultural Revolution. Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige became the most internationally recognized, but all five shared a similar background: years of labor in the countryside, military service, and a deep desire to redefine Chinese cinema through visual storytelling.

Why are Fifth Generation films banned in China?

Many Fifth Generation films were banned because they depicted the Cultural Revolution, rural poverty, and state oppression in ways that contradicted official narratives. Films like Farewell My Concubine and Yellow Earth showed the trauma of ordinary people under Maoist rule-not heroic struggle, but silence, submission, and loss. The government allowed some films to be shown internationally to boost cultural prestige, but kept them out of domestic theaters to avoid public questioning of history.

How did Zhang Yimou’s cinematography change Chinese cinema?

Zhang Yimou, who started as a cinematographer, invented the visual language of the Fifth Generation. He used bold, saturated colors-red, yellow, and black-not for decoration, but as emotional symbols. He framed scenes tightly to create claustrophobia, used wide landscape shots to show human insignificance, and relied on natural light to make even low-budget films look painterly. His work on Yellow Earth and Ju Dou proved that Chinese cinema could be artistically ambitious without state funding.

What’s the difference between Fifth and Sixth Generation filmmakers?

The Fifth Generation focused on historical trauma, using symbolic imagery and stylized visuals. The Sixth Generation, like Jia Zhangke and Wang Xiaoshuai, emerged in the 1990s and focused on contemporary urban life-factory workers, migrant laborers, and youth alienation. Their films are grittier, shot with handheld cameras, often in real locations with non-professional actors. Where Fifth Generation films were poetic and grand, Sixth Generation films are intimate and documentary-like.

Are Fifth Generation films still relevant today?

Absolutely. Their visual language-color as emotion, space as metaphor, silence as resistance-still shapes Chinese cinema. Even commercial films like Hero or the 2008 Olympics opening ceremony borrow their aesthetic. And for international audiences, these films remain essential for understanding modern China’s suppressed history. They’re not just old classics. They’re the foundation of how China tells its own story to the world.